Although African Americans faced strong institutional barriers, they nonetheless sought to utilize the building and loan association as a tool of capital accumulation for the working class. In 1899, W. E. B. Du Bois, who was then utilizing the latest statistical and social scientific tools to create the most detailed statistical and analytical portrait of African American life, looked optimistically to building and loan associations to aid in the advance of African Americans within American society.

The founding of at least thirteen such institutions was, according to Du Bois, “the most gratifying phenomenon” in the growth of African-American commerce and capital (Du Bois 13). The research and testimony of I. Maximilian Martin Jr. (whose father was active in the building and loan movement serving blacks in Philadelphia), confirms the popularity of these African American “community institutions” run as “part time affairs” from church basements and other locales in Philadelphia, enabling many migrants from the South to buy their first row house (Martin Jr., Oral History).

This progress, of course, took place in an atmosphere of hostility from many in the white financial establishment. As Maximilian Martin wrote in 1936, “our people were being insulted all over the city whenever they attempted to get reasonable housing” (Martin Sr., 2).

When we pay tribute to the cultural staying power of It’s a Wonderful Life, if we honor the ability of the many creative minds to create a narrative so faithful to the positive values in the American dream, we must also reckon with their concessions to popular prejudice. Until the civil rights movement began to gain new momentum in the late 1950s and early 1960s, African Americans were portrayed as the objects of light amusement (if not ridicule), entirely absent, or consigned to the deep background of a scene. Like Capra (and his lead character, George Bailey), Roosevelt was completely at home speaking of America’ s most recent immigrants as the quintessential representatives of a new chapter of the American dream.

…It is a difficult thing for those of us unused to notion of property to learn to save. Moreover, the national crime perpetrated in the mismanagement of the Freedman’s Bank had wide-spread influence in discouraging the saving habit. As it is to-day, there is not among all ‘these millions any far-reaching movement to encourage or facilitate saving except such local efforts as have arisen among themselves. While their extravagance and carelessness in the expenditure of their incomes is characteristic of the race, and will be for some time, yet there is some considerable saving even now,, and much money is invested. Land and houses are naturally favorite investments; and there are a number of red estate agents. It is difficult. to separate capital from accumulated wealth in the case of many who live on the income from rents or buy and sell real estate for s profit. Thirty-six such capitalists have been reported with about $750,000 invested. There are four banks in Washington D.C., Richmond, Virginia, and Birmingham, Alabama, and several large insurance companies which insure against sickness and injury, and collect weekly premiums. There are a number of brokers and money-lenders springing up here and there, especially in cities like Washington where there is a large salaried class. The most gratifying phenomenon is the spread of building and loan associations, of which there are thirteen reported….

There are probably several more of these associations not reported. The crying need of the future is more agencies to encourage saving among Negroes. Penny savings banks with branches in the country district, building and loan associations and the like would form a promising field for philanthropic effort. The Negroes, themselves, have as yet too few persons trained in handling and investing money. They would, however, co-operate with others, and such movements well-started would spread.

W.E.B. Du Bois, 13

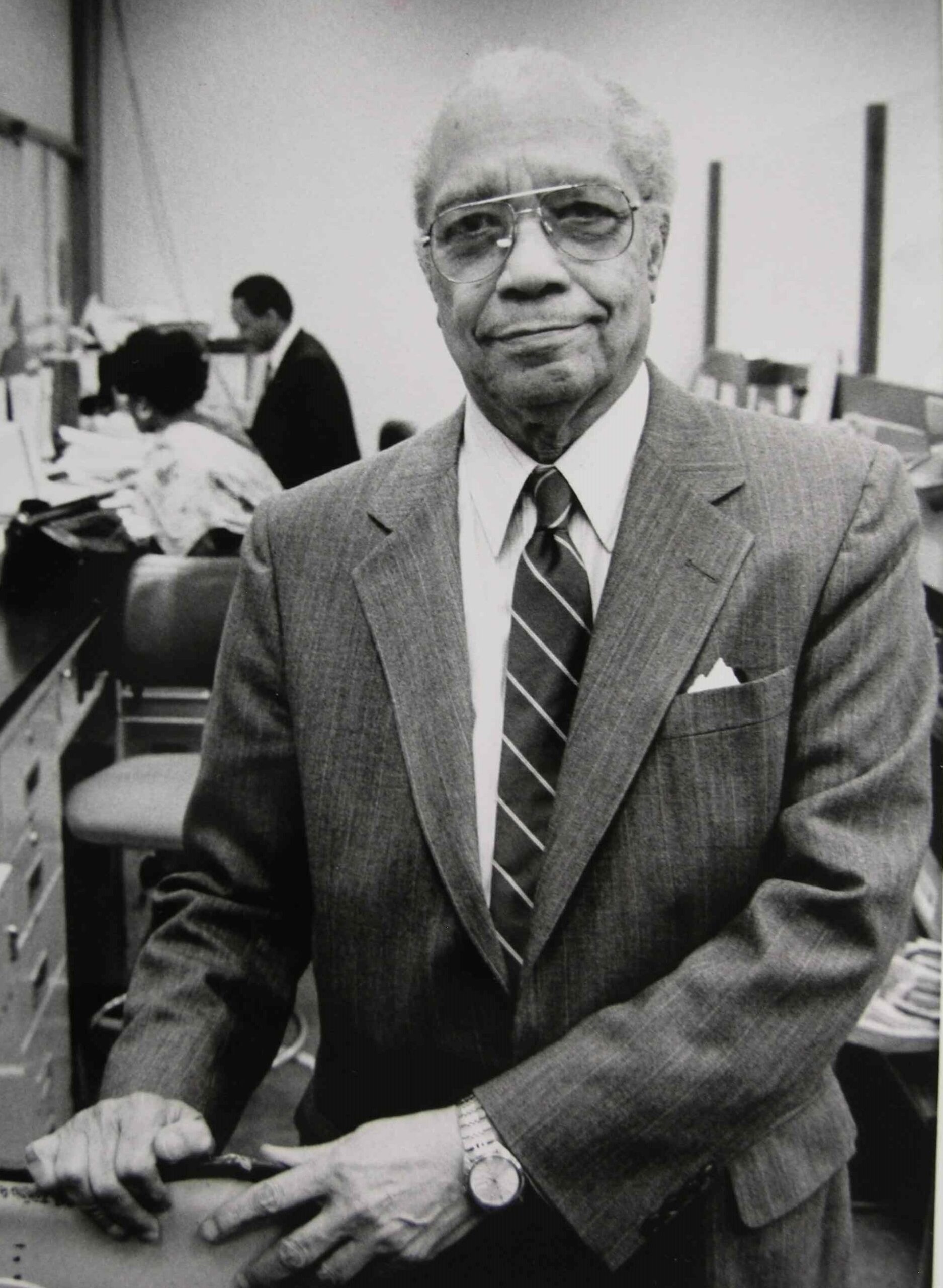

Isadore M. Martin

There now exist some oral histories which give us a very vivid idea of the barriers faced by African-Americans when it came to financing mortgages. Consider these comments from an interview with Isadore M. Martin Jr. (00:30:00 to 00:33:00):

HARDY: Now, were there white banks in the city that would fund mortgages?

MARTIN: There were a few, but they [pause] had very definite lending bias. Some of them frankly said, We will not lend on colored properties. There are some who would put in the mortgage a clause: that this property should not be occupied or sold to a member other than those of the Caucasian race. Very often in those days, your financing –[unintelligible]– was for three or five years, you’d pay interest only, and then you would have to renew it. And I remember on many occasions my father said, Now look, mail your monthly payment in. Don’t take it down to the bank or the insurance company. If they see you, they will call the mortgage. As some who didn’t have enough sense to follow his instructions found out. Normally, as long as the money is paid, you go along. But when you find somebody goes in, huh-uh. And as I say, I have seen, and we have had transactions, where there was a clause in the mortgage, not in the deed. Incidentally, restrictive covenants were never tested by law in Pennsylvania, but they universally existed. All new construction

HARDY: I think Baltimore pioneered that. I just read something.

MARTIN: Well, Louisville, and I think Baltimore. But uniformly, all new construction had a clause in there. They had: this property shall not be occupied, sold, or rented by any member of a race other than Caucasian–except as a servant. And unfortunately, in the early days of FHA, which was founded during the Roosevelt Administration, they aided and abetted…,they encouraged the insertion of these clauses. Were talking about the 1930s, now. Early 1930s, before World War Two, and FHA didn’t get itself straightened out until probably maybe ten years after World War Two. Because it helped perpetuate patterns of discrimination and segregation in residential living.

Questions for Discussion and Reflection

- In what ways did both the private economy and the public system of financial policies and regulations support racial discrimination?

Teacher’s Guide

Content Standard

- USH 4: The student will analyze the cycles of boom and bust of the 1920s and 1930s on the transformation of American government, the economy and society.

- B. Describe the rising racial tensions in American society including the resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan, increased lynchings, race massacres as typified by the Tulsa Race Massacre, the rise of Marcus Garvey and black nationalism, and the use of poll taxes and literacy tests to disenfranchise blacks.

Compelling Question #4: Why not housing for all?

This chapter presents well established evidence about the way racism infected not just the social system (race massacres), the political system (disenfranchisement) and the popular culture (lynching), but the economic and financial system as well.

Formative Performance Task

Review the script of It’s a Wonderful Life in light of the new information provided in this section. Write a memo to film director Frank Capra and his screenwriters telling him how you would change his script to take account of this history. Or would you?